Five insights from our large-scale benchmark

By now, you should be aware that our objectives are to overcome the high cost, duration, and risk issues in traditional de novo drug development pipelines. These are the reasons we study drug repurposing in the first place: automatically screening a set of drugs to find new therapeutic indications. For instance, a well-known (unintentional) example of drug repurposing is when thalidomide, which was introduced at first to treat morning sickness in pregnant women, is now featured against multiple myeloma. There are many approaches to screening drugs: for instance, some methods take into account the chemical structures of drugs and relevant proteins (protein-docking).

As a field that has led to several breakthroughs in research in recent years, machine learning has also been applied multiple times to drug repurposing. The most intuitive approach is to assume that there is a function of a specific shape that takes as input drug and disease information and returns a score correlated to the ability of the drug to treat the disease and find the values of the function parameters by learning from previously measured drug-disease scores, also called outcomes.

However, machine learning-based algorithms have to face numerous challenges in drug repurposing:

-

First, there are imbalanced outcomes: not all combinations of drugs and diseases have been tested in clinical trials; the set of accessible outcomes is relatively sparse. Moreover, fewer clinical trials with negative outcomes (the drug failed to show efficacy in treating a disease) are reported compared to positive clinical trials. This fact led us to consider collaborative filtering methods in our project, which are appropriate in that case. Those collaborative filtering methods try to find patterns in drug-disease associations across diseases that have been previously tested.

-

Second, publicly available drug repurposing data sets are hard for machine learning methods: they are often of small size and incorporate heterogeneous types of biological and chemical data (for instance, similarity with regards to drug chemical structures, proximity of gene targets in a genetic interaction network, etc.).

-

Third, there is no standard pipeline for the training and evaluating models for drug repurposing. Each research paper proposes its pipeline, with different algorithmic baselines to compare to and sometimes distinct validation metrics to quantify the performance.

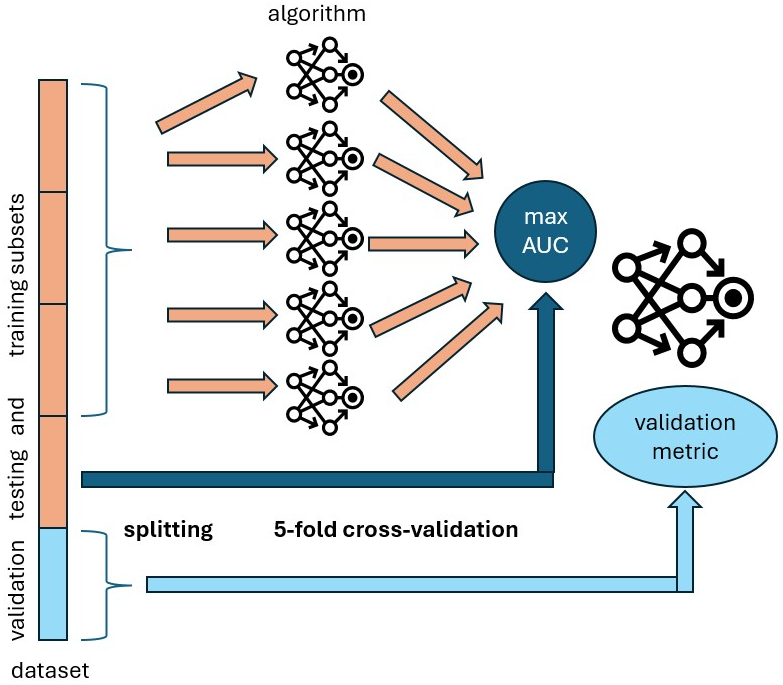

Our recently accepted paper [1] tries to tackle those questions. In that paper, we implemented an open-source benchmark procedure [2] using our packages stanscofi and benchscofi. Our benchmark is performed on eight publicly available drug repurposing data sets and eleven collaborative filtering methods (at the time of the publication of the paper). The process of training and evaluation of the models is shown in the figure below.

First, we split a data set into five sets of drug-disease outcomes of equal size. We use the three first sets (the training data) to train a collaborative filtering algorithm by splitting the training data into five subsets again, then training the model on four subsets and computing a validation metric on the last subset. Each subset is selected once as the validation subset. This procedure is called cross-validation and allows us to get the fairest evaluation of the algorithm’s performance on the training data. Finally, we select the trained model that achieves the highest value of the Area Under the Curve (AUC) validation metrics on one of the two held-out sets (named the testing set), which has not been used during the model’s training. We selected the AUC as a criterion because most papers from the literature also use this metric to train their models. Finally, we compare collaborative filtering methods according to their performance on the last held-out set, named the validation set.

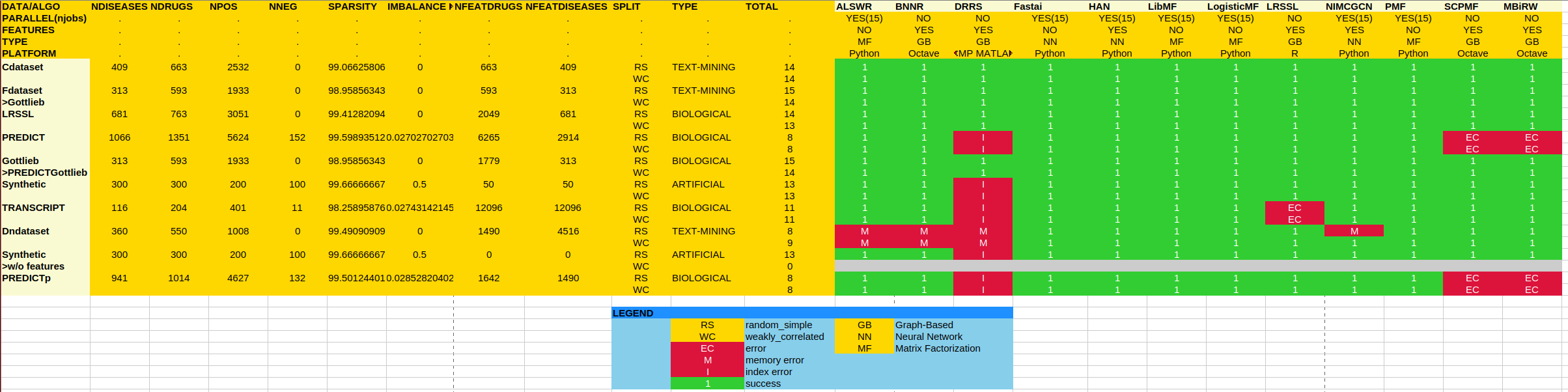

The current status of the benchmark is shown below.

As one can see, many runs with some of the collaborative filtering algorithms ended with errors (red cells), which is a measure of the reusability of the corresponding implementations. When a run at position (i,j) in the table successfully ended (green cell), it means that we could run 100 times (with different random seeds to take into account the variability of the data) algorithm number i on the data set number j. All numerical results can be found in [3].

It is now time to list our five insights from this large-scale benchmark! Of course, if you want further information, lots of plots, and statistics, please refer to our paper [1]!

1. Pairs or matrices?

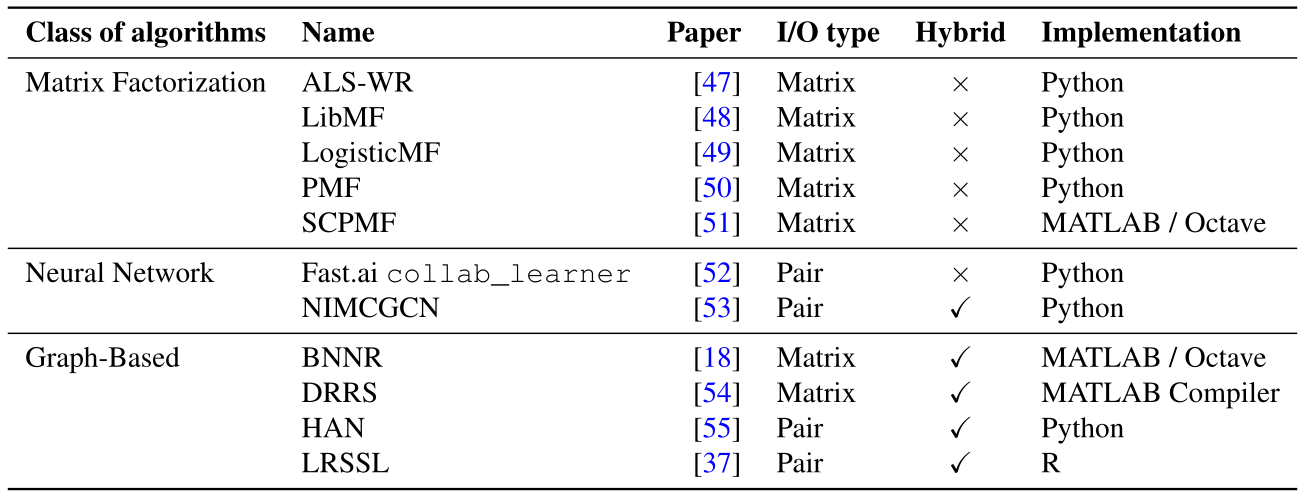

We distinguish two types of collaborative filtering algorithms in our benchmark according to what they take as input and return as output (column ``I/O type’’ in the table above)).

-

``Matrix-oriented’’: a matrix-oriented algorithm takes as input a matrix of drug-disease outcomes (where drugs are in rows and diseases are in columns), with possibly addition drug and disease information (if the algorithm is hybrid). The drug-disease outcomes are denoted with +1 (if the outcome is positive), -1 (if negative), or 0 (if unknown). Then, the algorithm fills the zeroes in the outcome matrix with either -1 or +1 and returns the completed matrix.

-

``Pair-oriented’’: a pair-oriented algorithm takes as input a pair of a drug and a disease, with possibly additional information about the drug and/or the disease, and returns the score associated with the pair (-1 or +1).

As one can see from the table, this type is independent of being a hybrid collaborative filtering (that is, using additional information about drugs and diseases) or of the class of algorithms, which correspond to the collaborative filtering technique implemented. In prior works, those algorithms are considered similarly, and recent papers propose both matrix-oriented and pair-oriented algorithms.

However, as we describe in our paper, a key difference between these two types of algorithms is that matrix-oriented algorithms get access to all zeroes in the outcome matrix during training if we are not careful during the data splitting, including those that are supposed to belong to the held-out sets. The consequence is that matrix-oriented algorithms fare better regarding predictive performance than other methods, but that is because they get access to some of the data on which they are evaluated during training. This issue is a problem known as data leakage in the machine learning community.

2. Optimizing for AUC does not guarantee good disease–wise, nor ranking performance

As previously mentioned, we compared several validation metrics used for collaborative filtering and/or machine-learning-based drug repurposing. In drug repurposing, the typical use case is to set a disease for which we would like to find a treatment and then screen all drugs for matches to that disease. As it turns out, the desired model’s performance will be, on average, good for all diseases.

As such, ``global’’ metrics such as accuracy -which is the number of correctly predicted outcomes divided by the number of known (not zero) outcomes- or Area Under the Curve might be inflated due to the presence of diseases for which a lot of outcomes are available (cancer subtypes, for instance) compared to more rarely studied diseases on which the model might perform extremely bad. As such, we favor local metrics (averaged across all diseases) and ranking metrics, where the score associated with a positive outcome as returned by the model must be higher than the score associated with an unknown or a negative outcome.

3. There is a need for more diverse reference drug repurposing datasets

We ran our benchmark on eight publicly available drug repurposing data sets from the literature. See this post, where we discuss the different data sets in detail. A good data set for drug repurposing should feature meaningful biological data and be challenging enough to benchmark the performance of the drug screening methods. In our benchmark, we show that the new frontier in making progress for drug repurposing is to beat the state-of-the-art on the three data sets: PREDICT, DNdataset, and TRANSCRIPT. Those data sets comprise drug and disease information which is closer to the biological setting (transcriptomics, interaction networks, etc.) compared to prior data sets and are sometimes more sparse, regarding the number of known outcomes.

4. Graph-based approaches perform best

Excluding matrix-oriented algorithms (due to our point 1.), we compare the two remaining classes of algorithms in terms of performance: neural networks and graph-based approaches, where connections between drugs and diseases are reconstructed. Our paper shows that this reconstruction might be a crucial asset to predict new therapeutic indications, as graph-based approaches outperform methods based on neural networks.

5. Be reproducible (please)!

We tried but could not reproduce the results shown in many papers from the literature, even in the presence of an open-source algorithm implementation, because of the lack of package versioning, unavailable random seeds, and so on. Then, for future works and research, we suggest using stanscofi and benchscofi to ensure more reproducible experiments and to benchmark easily with the state-of-the-art.

References

[1] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. Comprehensive evaluation of pure and hybrid collaborative filtering in drug repurposing. Sci Rep 15, 2711 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85927-x

[2] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. (2025). Benchmark code for “Comprehensive evaluation of pure and hybrid collaborative filtering in drug repurposing”. San Francisco (CA): GitHub; [accessed 2024 Sep 24]. https://github.com/RECeSS-EU-Project/benchmark-code/

[3] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. (2025). Benchmark traces/results for “Comprehensive evaluation of pure and hybrid collaborative filtering in drug repurposing”. San Francisco (CA): GitHub; [accessed 2024 Sep 24]. https://github.com/RECeSS-EU-Project/benchmark-results/