JELI: Joint Embedding-classifier Learning for improved Interpretability

We mentioned in a previous blog post the issues in machine learning for drug repurposing related to imbalanced drug-disease outcomes -that is, sparse results from clinical trials- and missing data -for instance, missing biological measurement on cells exposed to some drug. Remember that there are three categories of drug-disease outcomes in our drug-repurposing data sets:

-

Positive outcomes (denoted with +1) linked to a successful clinical trial: the drug is shown to treat the disease efficiently. This category makes for around 0.7% to 2.5% of all outcomes.

-

Negative outcomes (-1) are given by failed clinical trials. There might be several reasons behind the failure of a clinical trial: for instance, low accrual or toxic side effects. This category is even less represented in data sets, as often less than 0.3% of all outcomes are negative.

-

Unknown outcomes (0) constitute the vast majority of outcomes in public drug repurposing data sets (>98.5%). This large amount of unknown values is because there are many more possible drug-disease pairs than the number of registered clinical trials.

However, we cannot ignore the unknown drug-disease outcomes as they contain drugs that we want to repurpose, and because the set of known outcomes is too small to allow a machine learning method to learn the function predicting the matching between drugs and diseases. Moreover, negative outcomes might bring interesting supplementary information about that function, so we cannot ignore them. Finally, especially for healthcare, we are interested in explaining the predicted positive drug-disease pairs by linking the corresponding score the learned function gives to drug and disease biological information.

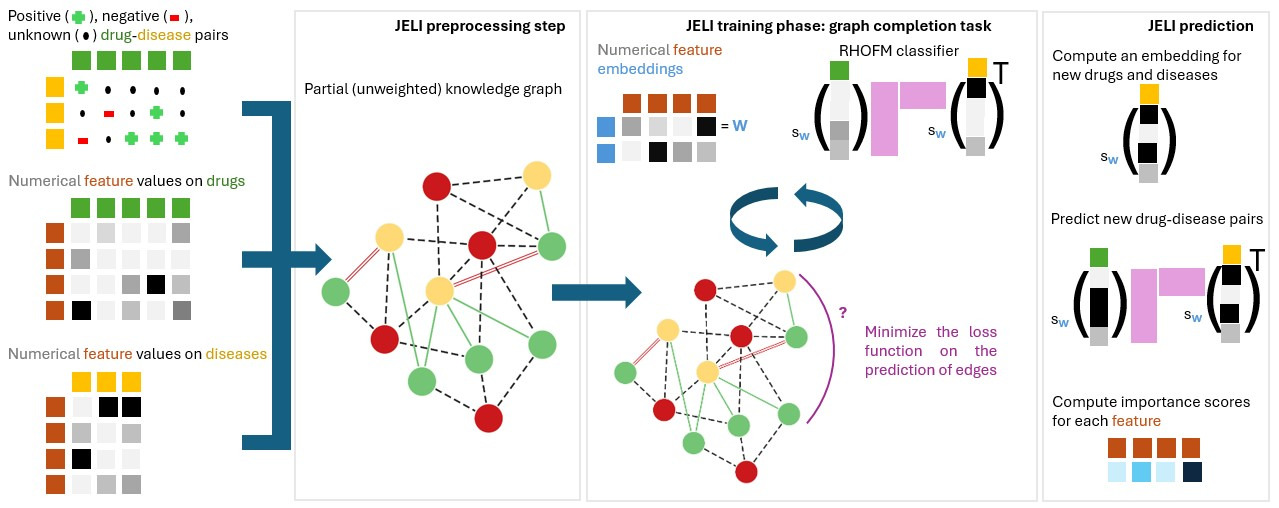

To solve these issues, we introduce JELI, a Joint Embedding-classifier Learning for improved Interpretability, in our recently accepted paper [1]. The figure below gives an overview of the pipeline related to JELI. This blog post will describe some of the highlights of this paper.

The main idea behind JELI is to reconstruct a knowledge graph, which combines all information known on drugs, diseases, and biological elements (for instance, genes). We start from a partial knowledge graph, where some edges are missing. To predict which edges are highly probable in the graph, we define a vector for each element, which captures meaningful information about that element$^1$ based on its neighbors in the graph and supplementary data about this element. Those vectors are called embeddings. Then, to predict whether the edge (a, b) is present in the graph, we compute a value that involves the embeddings of a and b. The higher the value, the more probable the edge. Once we learn the embeddings for all elements of the graph, we can reuse them to predict the edge between a drug and a disease! The cherry on the cake is that JELI can be used for any recommendation task (beyond drug repurposing), make predictions even for drugs and diseases unseen during training, and provide an explicit interpretation of the score associated with an edge, linking the probability of belonging to the positive class of outcomes to specific drug and disease information!

How does JELI work? Let’s go!

1. Structured classifier

First, we define the shape of the function that predicts the presence of an edge between a drug and a disease -that is, a classifier. To enable interpretability and flexibility, we define a structure on this classifier called a Redundant Higher-Order Factorization Machine (RHOFM). Traditional classifiers take a vector of information regarding a data point as input and output a score. Here, our vector of information is a combination of the embeddings of biological elements in the graph (any node that is not a drug nor a disease), which depends on the information on drugs and diseases regarding those biological elements. The expression of that combination is the structure of our classifier.

A simple example of structure is the linear one. That is, the information on drug A $x^A$ and disease B $x^B$ is

\[x^A = [x^A_1, x^A_2, ..., x^A_N] , x^B = [x^B_1, x^B_2, ..., x^B_N]\;,\]where $x^A_1, …, x^A_N, x^B_1, …, x^B_N$ are numerical values and $N$ is the number of biological elements in the graph. These information vectors might be related to genes, proteins, or measurements made on patients or cells exposed to a drug. Then, the linear structure of A and B concerning the embeddings of biological elements $W_1, W_2, …, W_N$ (which are vectors) is

\[W^A = x^A_1 W_1 + x^A_2 W_2 + ... + x^A_N W_N = \sum_{i \leq N} x^A_i W_i , W^B = = \sum_{i \leq N} x^B_i W_i\;.\]The RHOFM classifier is a function that has a linear term ($\omega_l^\intercal W^A$, where $\omega_l$ is a parameter to be estimated on the prior drug-disease outcomes, and M-wise-interaction terms which looks at interactions between each set of size M of biological elements, weighted by the corresponding values of those elements in the drug and disease information vectors $x^A$ and $x^B$. M varies between 2 and the prespecified order of the factorization machine (2, 3, 4, …).

2. Interpretability based on the structured classifier

The main asset of this structured classifier is that the contribution of each biological element to the score for a given drug-disease pair is (almost) straightforward. An importance score can be computed for each biological element. The value of the importance score of an element is correlated to the element drawing the outcome for that drug-disease pair towards the positive class. If the importance score for a given element e is positive and high for a drug-disease pair (A, B), then the drug A might act through the biological element e to treat the disease B. The same reasoning can be made when the importance score is negative and high: the drug A acts through B to trigger a toxic effect when given to a patient with disease B or might mimic disease B through the element e.

These importance scores can be computed based on whatever structure is assigned to the classifier.

3. Joint learning with embeddings

Finally, the classifier’s parameters and the embeddings are estimated together. For edges that are not between a drug and a disease, we select a well-known function that combines the embeddings of the two considered nodes of the graph [2] to score those edges. Finally, we aim to minimize a function that incorporates the principle that the parameters should maximize the score for edges already present in the knowledge graph.

We implemented the entire pipeline in an open-source Python package called jeli.

Experimental results

We performed several experiments with the JELI algorithm, some of which we report in this blog post. Our experimental code can be found at the following repository. Two main results are:

-

- Both the joint learning and the structure of the classifier contribute to the predictive performance of JELI.

-

- Embeddings on genes (from which interpretable scores are computed) can reliably reconstruct the 50 Hallmark gene function pathways.

We will refer the reader to the paper for Point 2. and develop further on Point 1. below.

Both the joint learning and the structure of the classifier are important

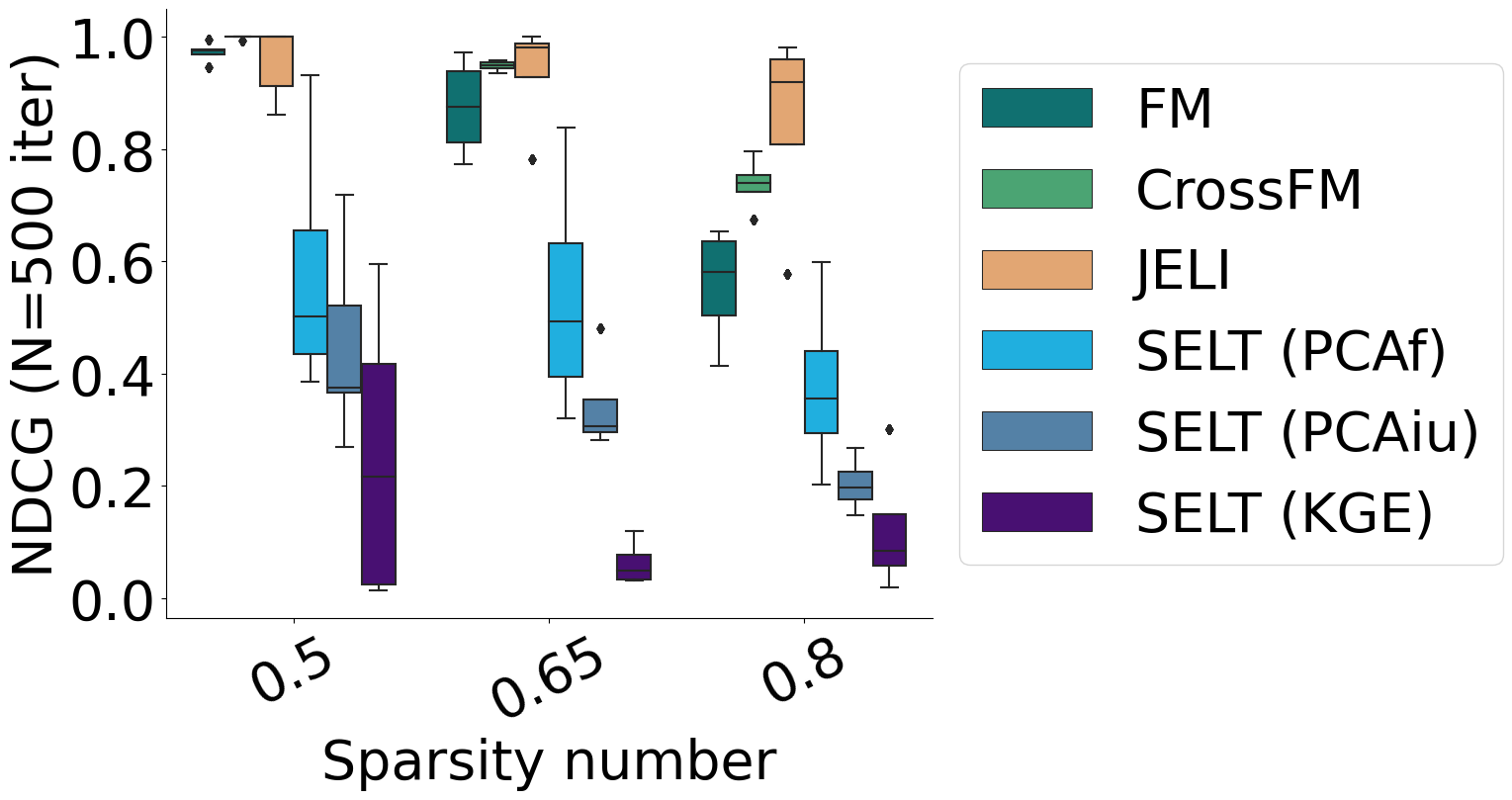

In this part, we remove the joint learning part (SELT variants, with different approaches to learning the embeddings independently from the classifier’s parameters) or the classifier’s structure (FM and CrossFM) from JELI and compare the performance of these variants to the performance of JELI. Have a look at the figure below.

As a validation metric, we use the average Non-Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) across diseases at a rank equal to the number of drugs in the synthetic data set we built. This measure is related to correctly ranking drug-disease outcomes -positive outcomes should have the highest scores, then unknown ones, and finally negative outcomes. We vary the sparsity, that is, the proportion of unknown outcomes in the synthetic data set.

We observe that joint learning is the most critical part of JELI, as removing it incurs a significant drop in predictive performance. However, the structure of the classifier is also crucial, as a lesser drop in performance can be noticed when removing the structure.

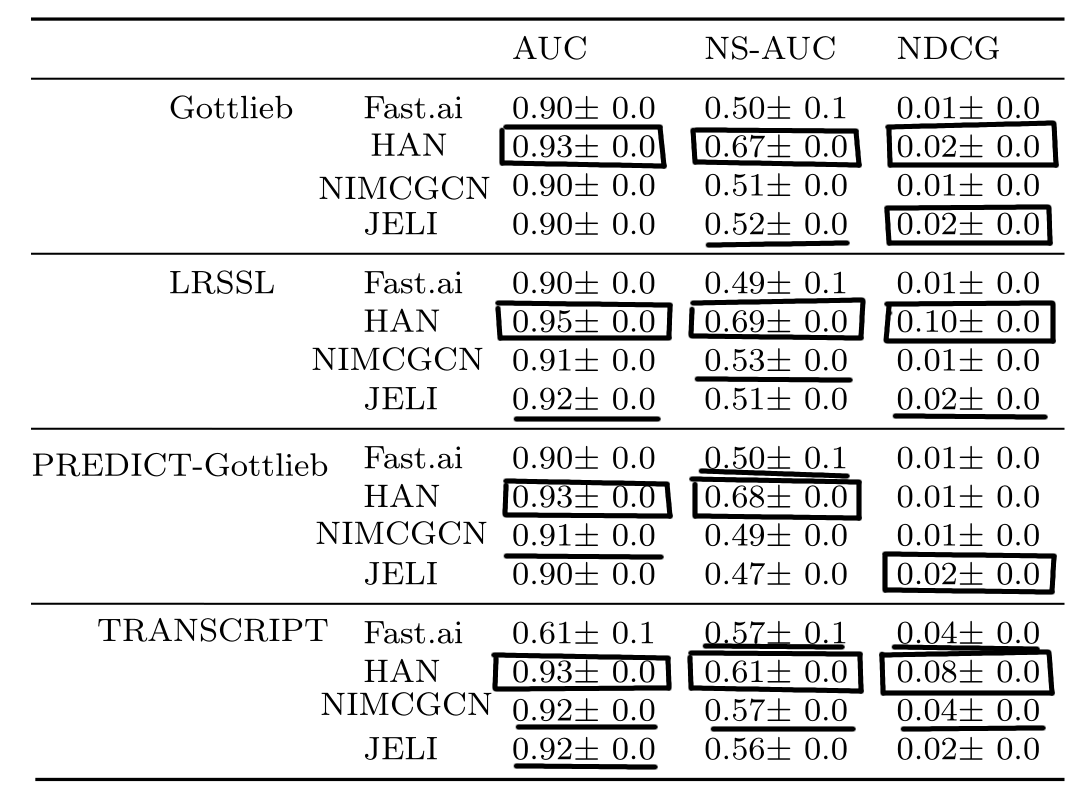

Drug repurposing task

Finally, we compared the drug repurposing performance on several public drug repurposing data sets with other recommender systems in the literature, which are also based on embeddings. See this post for more information about the drug repurposing data sets. We notice that JELI is regularly in the top two across data sets, in addition to providing interpretability as opposed to the state-of-the-art.

Conclusion

Our paper features many more experiments (related to the scalability of JELI, the impact of its hyperparameters, and many others!). The open-source implementation of the JELI algorithm can be found at the following reference [3]. The experimental code to generate the tables and plots is available at the following link [4].

We now close the second chapter of the RECeSS project (out of three). Our next project will feature the imputation of missing values in biological data! See you very soon!

Footnotes

$^1$ A bit a la Word2vec but on graph nodes instead of words!

References

[1] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. Joint embedding–classifier learning for interpretable collaborative filtering. BMC Bioinformatics 26, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-024-06026-8

[2] Balazevic, Ivana, Carl Allen, and Timothy Hospedales. “Multi-relational poincaré graph embeddings.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019).

[3] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. (2025). Code for the JELI algorithm described in “Joint embedding–classifier learning for interpretable collaborative filtering”. San Francisco (CA): GitHub; [accessed 2025 Jan 22]. https://github.com/RECeSS-EU-Project/JELI/

[4] Réda, C., Vie, JJ. & Wolkenhauer, O. (2025). Experimental code for “Joint embedding–classifier learning for interpretable collaborative filtering”. San Francisco (CA): GitHub; [accessed 2025 Jan 22]. https://github.com/RECeSS-EU-Project/JELI-experiments/